|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||

|

Clyde G. DurhamPineville, Louisiana- "Up until a few months prior to our arrival, most B-29 missions were during the daylight hours, but now that the Chinese Communists were into the war their better experienced MiG-15 pilots were really beginning to take a toll on B-29s. On one mission a few months before we got there, we were told that on one five-plane B-29 raid, four of them were lost to MiGs." - Clyde Durham

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

A Tailgunner's View of the Korean War

|

|||||||||||||||

| And so it begins...

First USAF bombers on the offensive were 12, Douglas B-26 attack bombers from the 8th Bomb Squadron. They hit rail yards at Musan early on the 28th of June. That same afternoon, four B-29s from the 19th Bomb Group (BG) out of Kadena Air Force Base on Okinawa hit roads and railroads just north of Seoul. The 19th BG was made up of the 28th, 30th and 93rd Bomb Squadrons and was permanently based at Andersen AFB, Guam. Less than 24 hours after being alerted, the 19th BG was at Kadena and preparing for their first combat mission over Korea. They had been told to take enough clothing and personal items for "a few weeks." No one dreamed that 37 months later, the 19th would still be at Kadena. It was the only one of the three original B-29 bomb groups to fly combat for the entire war. Trial by fire for the new Strategic Air Command (SAC)... As the war began, in addition to FEAF's 19th, SAC sent the 22nd and 92nd Bomb Groups, also equipped with B-29s. In May of 1952 the three B-29 groups flying combat were: two at Kadena, the 19th and SAC'S 307th and the 98th, also SAC, which was based at Yakota AFB near Tokyo. That same month a replacement crew, headed by Aircraft Commander Capt. H.M. Locker, prepared to fly from California to Kadena AFB, reporting for a tour of duty with the 28th Bomb Squadron. I was the left gunner on that crew. We had orders to fly a re-conditioned B-29 from McClellan AFB to Kadena but after waiting 10 days with no plane being ready, our orders sent us to Travis AFB and a day later we left on a C-54 ambulance aircraft that shuttled between Korea and the states. They flew wounded GIs home and returned to the Far East with replacement personnel. We spent about 24 hours at Hickam AFB in Honolulu then made the remainder of the trip in a couple of hops. After reporting in at 28th Bomb Squadron headquarters, we were assigned barracks, flight gear and attended orientation. This all took the better part of a week and then we began flying training missions. The training included very little formation flying, which was unexpected by us, but was long on navigation and radar bombing using SHORAN as well as LORAN. We soon were told why. MiG-15s take their toll on the Superforts... Up until a few months prior to our arrival, most B-29 missions were during the daylight hours, but now that the Chinese Communists were into the war their better experienced MiG-15 pilots were really beginning to take a toll on B-29s. On one mission a few months before we got there, we were told that on one five-plane B-29 raid, four of them were lost to MiGs. |

|||||||||||||||

First Mission on the night of Friday 13th... As a result of the Mig-15 attacks, strategy was changed and now we were flying almost 100 of our combat missions at night. In fact the undersides of less than half our B-29s had been painted black. It wasn't until after we had flown four or five missions that all the B-29s at Kadena had been coated with black paint on their undersides. After flying the orientation training missions we were cleared for combat and told that our first mission would probably be in the next three or four days. The procedure in the 28th was to post the names of crew members and their aircraft on the bulletin boards in the barracks daily for the following nights mission. This was done about 24 to 28 hours prior to scheduled takeoff. Since we knew we would soon be on a mission we were joking about flying it on Friday, the 13th! On Thursday afternoon, 12 June 1952 word quickly spread that Friday's combat roster had been posted. A friend stuck his head in my room, we were bunked two to a room, and told me my name was on the list. I made a fast trip to see for myself and there it was! It was as though my name was typed in inch-high capital letters and highlighted with a spotlight. I'm sure my heart paused for a few seconds. My first combat mission and on a Friday, the 13th!

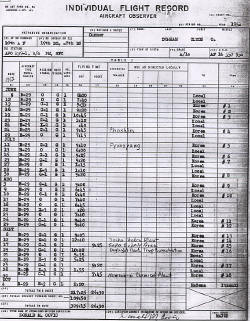

I remember very little about my first mission other than it was relatively routine. A total of nine hours and 35 minutes were logged and we encountered a little light flak. Otherwise it was uneventful except for the fact it was my first combat mission and that alone made it memorable for me! Takeoff was around 1800 and we touched down back at Kadena at 0335.We went to debriefing at 19th BG headquarters then back to the hardstand to remove and clean all our .50 caliber machine guns. Even though on that mission we never fired them at a MiG, all guns had been test-fired before we reached landfall over the South Korean coast. Back to the barracks shortly after daylight. Sleep finally came but I was so keyed up it took awhile to drop off. Plenty of firepower...

The B-29 had five remote controlled turrets that contained a total of twelve .50 caliber machine guns. The upper forward turret held four guns and there were two weapons each in the upper aft, lower forward, lower aft and tail turrets. The gunnery system on the B-29 incorporated switches that allowed a gunner to control not only his primary turret but take over certain other turrets in the event another gunner was knocked out of action. Primary turret for the bombardier was the upper forward turret but by flipping a couple of switches, he could take over the lower forward, controlling both or either one. The right gunner had primary control of the lower forward but he could also fire the lower aft and/or the tail guns. As left gunner, I had the lower aft as my primary turret, but could also fire the lower forward and/or the tail guns. The CFC, or top gunner, had the upper aft as his primary but could also control the upper forward. The tail gunner had primary control of the tail guns. The mission routine... With the exception of one daylight raid, the order for a combat mission went something like this: Notification of being scheduled for a mission was posted about 24 hours prior to the mission. The morning of the scheduled mission we four gunners would catch the 6x6 shuttle truck to the 28th BS Headquarters/Operations quonset huts. Then we caught a different shuttle that ran to all the 2801 BS hardstands. These were World War II hardstands and were really spread out to minimize damage from bombs or strafing attacks. Once at the hardstand of our aircraft we would load and/or check the ammunition in all gun turrets, inspect our .50 caliber machine guns, set head spacing on them, then install them in the turrets. Following that we did a complete ground check of all our electrical equipment and computers that directed our remote-controlled gun turrets. The final stage of our gun preflight was to arm the guns and then point the weapons in the upper turrets at about a 45-degree angle upward and the lower turret guns about 45-degrees down. This told everyone that all the guns on the aircraft were "hot" and to be very careful in turning on any electrical power or fooling with the turrets in any way. Once we gunners finished our early preflight, which usually took two to three hours, counting travel time, we went back to the barracks area, ate lunch in our 24-hour mess then tried for a nap and a shower before getting ready for mission briefing at group headquarters. The briefing and pre-flight... Briefing was usually between 1400 to 1600 hours and following it our aircraft commander, navigator, bombardier, radar operator and radio operator went to shorter, specialized briefings. The pilot, flight engineer and four gunners went to the aircraft for another pre-flight, this one concerning checking and running up the engines and inspecting the airplane in general. After the arrival of the remainder of the crew and the completion of their individual pre-flights, we lined up for crew inspection. Each crew member had a parachute, Mae West life jacket, one-man rubber dinghy, oxygen mask, helmet, head set, hand held and throat mike, flak jacket plus the individual's choice of fleece-lined boots, jackets, pants, etc. Even though we were pressurized and had heat for the crew compartment, it still got pretty cold at altitude. Flight lunches and thermoses of water were delivered to the aircraft as we were pre-flighting. The meals consisted of two per man. One was fresh (sandwiches, piece of fruit, bag of chips, sometimes a cookie or candy and a bag with salt, pepper, sugar and a packet of instant coffee) plus an emergency ration box, called the 1F-4, containing a can of meat or cheese, a can of fruit, stack of crackers and salt, pepper, gum, coffee, toothpick, etc. The fresh lunches were all the same (pretty good most of the time), but the IF-4 boxes varied from pretty good to terrible. The ones containing a can of cheese, boned chicken or ham were the favorites of most of us as was the cans of fruit and those of crackers. Over a period of time we would build up a personal supply of IF-4s that we kept in our rooms and ate at times when we didn't feel like making the hike to the mess hall or the times when we were confined to barracks for a few days because a typhoon was doing its best to drown or blow away everything on the island. I remember one time when a typhoon hit and our plane was not flyable so we rode out the storm on the island. They had sent word the mess hall would close in an hour and would not reopen until the typhoon passed. We decided to try for one last hot meal. Boy, was that a mistake. It was raining so heavy and the wind blowing so hard that we were soaked and had some of our clothing blown away before we went 20 feet. The rain, driven by the wind, felt like someone was shooting pellets of gravel at us. We finally gave up any attempt to make the mess hall and staggered back to the barracks and ate IF-4s for the next two days. We later found out the weather station had recorded winds of 198 MPH!

Third combat mission on Command Decision... On our third combat mission we were assigned to fly an aircraft named Command Decision, arguably the most famous B-29 of the entire Korean War. Command Decision flew many combat missions over Japan in World War II and over Korea but it became famous for the five MiG kills it was credited with. The 28th Bomb Squadron's Command Decision was the only B-29 of the entire Korean War to shoot down five MiGs. This occurred, of course, before we arrived at Kadena, but the aircraft commander when all those MiGs were shot down was Capt. Donald Covic. When his crew's tour of duty was up, Capt. Covic signed up for another tour and was the Operations Officer (and had become a major) when we became a part of the 28th. There was a popular story told in the squadron about the MiG victories. It was said that Capt. Covic and the crew were on a daylight mission when they spotted a MiG- 15. They shot at two MiGs, claimed three, got credit for four and then painted five kills on Command Decision. Of course, this was said with tongue planted firmly in cheek! Observers outside the crew verified all five kills. Perhaps even more amazing was the fact that three of those five kills were scored on one mission, two by the right gunner and one by the tail gunner. Runway mishap grounds the war’s most famous bomber... Almost a week after our third mission on Command Decision four crews, including us, flew a two-hour training mission in the local area. We were the first aircraft to land and the current crew of Command Decision followed us. All four planes landed and followed each other on the taxi strip heading to the 28th hardstands. We were about half way there and I happened to be looking back at Command Decision and at that moment I saw the nose of the airplane plunge to the taxi strip and all four props on the big 3350 Wright-Cyclone radial engines dig into the taxi strip. We found out that the taxi strip had given way under the nose gear and dropped about 10 or 12 inches. The sudden stoppage of the nose gear and the forward motion of the airplane collapsed the nose gear. Major Covic was at his desk when word of the accident reached him. He immediately hopped into his jeep and went to the scene of the accident. It was several hours before he finally got back to squadron operations and when he walked in the first thing he saw was the "Command Decision" model resting on its nose on his desk. Someone had pulled off the nose gear! Maj. Covic left it that way until the real aircraft flew again, almost three months later. Our crew had flown a different airplane on each of our first three missions but shortly after that we got word

that we were assigned our own aircraft. At that time the Air Force still had a team concept of a unit consisting

of an airplane, with the same ground crew and flight crew. The only time this varied much was if a plane was down

for maintenance, the flight crew would make their scheduled mission on another aircraft. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| The Apache's last mission...

We learned from a member of Apache's ground crew that the mission that night was to be the last of that flight crew's tour. The next day they would begin processing for their return to the USA. Our crew was next in line to put Apache on the warpath again. We hung around the hardstand for awhile, took some photos and visited with a couple of guys on the ground crew. They were very proud of their airplane. The next morning we got the grim news. Apache had gone down the night before with the loss of all crewmembers. The crew of the plane following Apache in the bomber stream told the sad tale of Apache's last mission. Apache had passed the IP and was on the bomb run. The crew following them said that Apache was maybe half way between the IP and the bomb release point when suddenly the night sky was lit up by a gigantic fire ball. Apache had suffered a direct flak hit and the 20,000 pounds of bombs and 3,000 gallons of high-octane fuel exploded. The airplane and her entire crew were instantly vaporized in the monstrous explosion. [KWE Note: Apache actually survived and landed safely. There were no fatalities.] Engine troubles make for risky business... Two days later we were assigned Top Of The Mark. This B-29 was named after the cocktail lounge on the top of the world famous Mark Hopkins hotel in San Francisco . To this day, any veterans who flew her are still honored with a free drink at the Top of the Mark's bar. Our fourth combat mission on 24 June 52 was number 112 for Top Of The Mark. Almost half of those were over Japan in during World War II in 1945. The rest were over Korea. We flew her on 14 combat missions before she was sent back to the states for overhaul. This was after our 17th combat mission on September 25, 1952. We took off on this particular mission grossing 140,000 pounds, which was normal for all our missions. The original B-29 design called for a maximum gross takeoff weight of just 120,000 pounds. We had the usual bomb load of forty 500-pounders (twenty in each bomb bay) and every pound of fuel we could cram in. Normal procedure was to fly from Okinawa at 4,000 feet to conserve fuel until we made landfall over the southern coast of Korea . Then begin our climb to bombing altitude. About 45 minutes after takeoff number three engine began running rough and we had to shut it down and feather the prop. After a brief discussion in the cockpit the aircraft commander (AC) decided to continue the mission on three engines, at least until something happened to make him change his mind. We managed to maintain our altitude and even gain some, but there was no way we were going to get up to 20,000 feet, the scheduled bombing altitude for our primary target. Almost the entire length of this mission was flown on three engines. There is a reason why they hung four of those 2,200 HP Wright-Cyclones on a B-29. Lose one, and this magnificent flying beast will still take you to the target and safely back to base. These aircraft were a flying testament to the brilliance of American design, the innovation of our engineering, the quality of our manufacturing and the dedicated craftsmanship of the men and women who built them. The AC decided to divert to the secondary target and bomb from as high as we could get which was somewhere near 6,000 feet. The secondary was just over the 38th parallel in North Korea. We managed to drop our bombs and head back to Okinawa without further incident although I'm sure the remaining three engines didn't appreciate it very much. Our AC was later awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for this and the other 10 of us were rewarded by aging a few years each in a matter of hours. Several missions later we were presented with the opportunity to duplicate the three-engine mission feat. We lost an engine about 30 minutes after take off and the AC again decided to go for it on three. This time his/our luck didn't hold. Shortly after shutting down the first engine, another one began running rough. Just before feathering the prop on the second bad engine we quickly dumped our bombs in the ocean (we hadn't even armed them yet) and made a 180-degree turn and headed back to Kadena. We made it back, declared an emergency and made a straight-in approach to Kadena on just the two remaining engines. We landed without any further incidents and taxied up to our hardstand. Our ground crew had been alerted and was waiting for us. Tears were running down the cheeks of the crew chief, a Master Sergeant veteran of WWII. He said this was the first abort of a combat mission for Top Of The Mark in almost 100 scheduled combat flights dating back to Japan in WWII. Obviously he was sad, but quickly stated he did not blame us. He said, We'll just start a new string. Flying Top of The Mark through a typhoon... One of my most unusual, and sometimes scary, times was one in which the B-29 we were in never left the ground. Typhoons hit Okinawa on four different occasions during our tour. On most of them we evacuated the planes to Guam . But one time, for some reason unknown to me, we and our planes were still on the ground at Kadena when a typhoon hit the island. As usual it was raining so hard you felt as though you were under water. I was born and raised in Louisiana where we usually had heavy rains and hurricanes, but I never went through anything like I experienced on Okinawa. We got word at the barracks for the left and right gunner and the flight engineer of all crews to report to their aircraft immediately bringing every thing we normally took on a mission except the flak vests. When we got to Top Of The Mark the rain was getting heavier and the wind stronger. Our AC and pilot had just gotten there and they told us what we'd be doing for the next 24 hours or so. The five of us, along with three or four of our ground crew, would quickly preflight and board the aircraft. We would then start the engines and fly the plane on the ground, keeping it headed directly into the teeth of the typhoon. Controls were unlocked, engines were running and the AC and pilot were using the flight controls as though we were airborne. On occasional trips to the cockpit I observed the air speed indicator touching on close to 150 knots and blipping higher while we weren't moving more than a foot or two at the most backward or forward. They controlled that with the throttles. I found out this was a technique developed late in WWII when there were hundreds and hundreds of B-29s in the Far East theatre of operations and the only bases large enough to handle the big bombers were crammed with them, leaving no place to go when a typhoon hit. We spent about 24 hours at this, getting a few breaks when the wind lessened and later when the eye of the typhoon passed over the island. It was one of the stranger experiences I ever had involving a B-29 but it saved our aircraft when the potential for large damage was clearly there. Only minor damage occurred to any of our planes, mostly when the savage winds blew objects into a plane. Top Of The Mark gets shot to hell over MiG Alley... Our combat missions averaged about nine and a half hours flying time with our longest being 12 hours, and the shortest 8:05 . Since all but one of our missions was flown at night and the North Koreans and Chinese Communists didn't have a lot of radar- equipped MiG-15s; we didn't have to worry too much about fighters. Anti-aircraft fire was another story. Depending on the target, the enemy's radar- controlled guns and searchlights ranged from very light to very heavy. From our crew's point of view our worst mission was our 18th, on September 30, 1952 . Our target that night was the Namsam-ni Chemical Plant.

Our aircraft was well back in the main bomber stream. We were flying for the first time since Top Of The Mark had been sent back to the states. Our aircraft was a recently reconditioned B-29 fresh from the states and this was its first flight since arriving at Kadena. The aircraft was in good shape but it felt very strange after flying Top Of The Mark on every combat mission and training hop for over four months. On this mission our bombing altitude was 27,500 feet, the highest of any of our missions over Korea . Since we were so far back in the bomber stream the guns and searchlights were pretty well zeroed-in on us, even though all aircraft were not scheduled over the target on the same heading, altitude or time separation. As we turned on the IP, we could see the lights and guns picking up each B-29 as it neared the target area. When we closed on the target, we began picking up anti-aircraft fire and searchlights. At first they weren't close but they rapidly began getting our range, speed and altitude. We could hear shrapnel rattling on the skin of the airplane. Suddenly, the searchlights locked on us. We immediately felt naked and exposed, as though the whole world was looking at us. The interior of our B-29 was brighter than full daylight. Just a few minutes from the bomb release point we felt, heard and saw a huge explosion in the left wing near the rear of number one engine nacelle. A large stream of smoke poured back from number one engine and the left wing went up and the right down from the force of the explosion. I reported the smoke just as another explosion hit us on the underside of the plane between the lower aft turret and the tail compartment. This was immediately followed by a flak burst under the right wing. The second and third hits were not as strong as the first one but they were strong enough to get our attention. We were locked in searchlights and the anti-aircraft guns were right on our altitude and course. The AC gave the order to salvo the bombs so we could get the hell out of there! The bombardier had a salvo switch in the nose and we had one in the gunner's compartment. Capt. Mohr immediately hit his switch and nothing happened. The CFC gunner had climbed down from his position and flipped our switch. Still, not a single bomb dropped. This is what's known as a very high pucker moment. We were still locked in lights and catching shrapnel. The AC gave the order to prepare to bail out. The next command would be, "Bail out!" We were deep in North Korea , hundreds of miles behind enemy lines, searchlights and guns were locked on us. Flak was still peppering the aircraft and with 20,000 pounds of bombs plus 3,000 gallons of fuel remaining, we could follow Apache into oblivion at any second. I was anxious and worried but the only thing really on my mind in those few seconds was, "We're going to have to bail out and as I'm floating down in my parachute one of those anti-aircraft shells on the way up is going to go right through me on my way down!" It wasn't until much later, after we were out of danger that I realized there were many other unpleasant things more likely to happen to me than being pierced in mid-air by an anti-aircraft shell! It has taken a lot longer to read all this than it took for it to happen. The actual time could be measured in seconds. Fortunately we never got the final bailout command. Suddenly, one of the salvo switches worked and all 40 of our 500-pounders dropped instantly. Relieved of that 20,000 pounds of weight in a split second, the B-29 surged several hundred feet upward. At the same time, the AC racked the plane hard over on its left wing and into a sharp descent. We lost three or four thousand feet very quickly. The searchlights and guns left us far behind. The AC quickly began a crew check as he leveled off and no one had a scratch! The aircraft was not so lucky. Smoke was still streaming back from the left wing. The flight engineer, in checking his instrument panel, reported an almost total loss of fuel from number one wing tank. We realized then that it was vaporized fuel and not smoke that had been streaming back from engine number one. The miracle was there was no explosion after the hit and no huge fireball to consume our bomber. With all the fuel lost from that tank we didn't have enough remaining to get back to Okinawa so we diverted to Itazuki Air Force Base near Fukuoka on Honshu , the southernmost island of Japan . The next day we all got the shakes after seeing the four-foot by two-foot hole blown completely through the left wing, almost directly through the center of the number one fuel tank. God was truly protecting us that night! The Air Force decided to cannibalize the aircraft because of structural damage. We really missed Top Of The Mark but at least it was proven again that a B-29 could be pretty tough, much like its older sister, the B-17. Fighter pilots get a flyby... Itazuki was a jet fighter base. A lot of the F-86 Sabre jet pilots were kidding our AC and pilot. They complained that our big old obsolete bomber was tarnishing the reputation of their sleek jet fighters just by sitting there with them on the ramp. Capt. Locker and Lt. King suggested those fighter boys come watch us take off in that big old bird. The next day at 1000 hours, 20 or 30 fighter pilots and assorted personnel were on the ramp watching our engine start up. The main runway at Itazuki was about 8 or 10,000 feet. The B-29 we were flying back to Kadena was relatively light. No bombs, no ammunition, only enough fuel to get us home and just our parachutes and the weight of the crew. After engine run-ups and checks. Locker positioned the B-29 at the very end of the runway. He held the brakes and applied takeoff power to those big radials. He let the plane shudder and shake until he was assured he had maximum RPM. Then he released the brakes. That light B-29 surged down the runway and about the halfway point he pulled it off the ground. With just 10 feet of altitude, he gave the gear-up command. The gear sucked up and he held the plane just a few feet off the ground for the last half of the runway. Just as we neared the end of the runway he pulled the wheel back and began a pretty sharp left turn. He got up to a couple hundred feet and roared over the assembled pilots on the ramp. I looked down and saw big grins and waves as we passed over them. Locker said, That ought to show those guys what a real airplane can do. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| A nerve-wracking tailgunner mission... The reason I was in the tail of our B-29 on a combat mission was very simple. Our regular tail gunner was DNIF (Duty Not Involving Flying) because of a severe head cold. When our Aircraft Commander was notified of this, he asked us if there was a volunteer to fly the tail. I had never flown the tail on a combat mission, so I immediately piped up and said, "I'll take Smitty's spot, Capt. Locker." And that was the beginning of a very memorable mission, at least for me if not the rest of the crew. On a B-29 there are three pressurized compartments; the forward crew compartment which housed the bombardier, aircraft commander, pilot, flight engineer, navigator and radio operator. That pressurized compartment began at the nose and ended at the forward bulkhead of the forward bomb bay. It was connected to the aft pressurized compartment by a 40-ft. long tunnel along the top of the aircraft that spanned both bomb bays. The tunnel was also pressurized. The aft pressurized compartment began at the forward bulkhead door at the rear of the aft bomb bay and included the positions of the CFC gunner, left and right gunners and the radar operator. This gunners pressurized compartment ended at a rear bulkhead door just forward of the Auxiliary Power Unit. The third pressurized compartment was the tail gunner's completely separate compartment at the very rear of the aircraft. It began at the tail gunners bulkhead door and ended just a couple of feet away at the back end of the twin .50 cal. machine guns that comprised the tail turret. This was a tiny space large enough for the tail gunner to squeeze in and that's it. The tail gunner even had to wear a chest pack parachute but it had to be left outside his compartment due to space restrictions. Fortunately the tail gunner was not required to stay in his position on takeoffs and landings nor did he stay back there usually if the altitude was under 10,000 feet and the aircraft was unpressurized. His duties prior to the pressurization of the aircraft was to start up the Auxiliary Power Unit in the aft unpressurized compartment and monitor its output until the aircraft was airborne. Once we were aloft and our engines were generating all the electrical power required the Aircraft Commander would notify the tail gunner to shut down the Auxiliary Power Unit (universally called the Putt-Putt by flight and ground crew alike!). When the tail gunner had completed this task he then went forward to the Aft Gunners Pressurized Compartment where he stayed until we began our climb to bombing altitude and the Flight Engineer would begin pressurizing the aircraft. That's when the tail gunner went back to his compartment and remained there until the aircraft was depressurized again. Depending on the length of the mission the time the tail gunner spent in his tiny compartment could be up to four hours or so. After take off we would fly toward Korea in a bomber stream. We would hit the same target with multiple B-29s coming in with a 500 foot separation and about a 45 second interval. When we reached landfall the Aircraft Commander called me and said it was time to go back to the tail and get ready to pressurize. I'll try to describe the tail gunners compartment. The gunner crawled on his hands and knees into his compartment thru the bulkhead pressure door and then reached around behind himself to pull the door closed and latch it securely. The door hinged inwardly into the tail gunners compartment and was concave in shape, not flat. It, as all the bulkhead doors, had a small center circle of glass so one could see thru it into whatever compartment one was looking. Once in the tail gunner's compartment with the bulkhead door secured, the flight engineer could then began pressurizing the aircraft. Regardless of the actual altitude the interior pressure of the aircraft was usually held to 10,000 feet or slightly under. Everyone is accustomed to flying in pressurized aircraft today but when the B-29 was designed, that was a novelty on production aircraft, especially combat airplanes. After I was in the tail gunner's compartment and had the bulkhead door secured I pulled down the seat. The back of the seat was on a sliding rail and the seat part was spring-loaded and hinged to remain flat against the back of the seat. With no small amount of difficulty I was able to get the seat in position and get myself in the seat. I then reported in via intercom that I was in position and ready for pressurization. I was 21 years old and stood about 6'1" and weighed about 185 lbs., several inches taller and about 30 lbs. heavier than Smitty, our regular tail gunner. There was perhaps about three inches between my shoulders and the sides of the tail gunners compartment and maybe six or eight inches between my face and my gun sight. And I would have to stay in that confining position for perhaps four hours or even a little longer. Today, at age 72, I could not remain in that position for longer than four minutes. I get very claustrophobic now just thinking about it. Even though it was a tight fit and very confining, the view from the tail was unbelievable. The trailing edges of the horizontal stabilizer were forward of me and I had the feeling of literally being outside the very tail end of the aircraft. It was pretty dark by the time we reached the 38th parallel. By late 1952, the fighting had pretty much stabilized to shooting at each other along a line along the 38th parallel. We were at an altitude of 17,000 feet. As we flew over the imaginary line it was impossible to miss. Everything on the ground above and below the front lines was totally blacked out but the line itself looked like a line of fire from horizon to horizon. Of course I had seen this from my left gunners position on all our previous missions but that was like just seeing half the picture. From the tail I could see the guns firing and the explosions from horizon to horizon. This occurred over 50 years ago and I still have that image burned into my memory. At 20,000 feet on a dark, cloudless night over enemy territory it's incredible how many jet fighters I could see making a pass at our bomber. Fortunately, the vast majority of those "fighters" turned out to be shooting stars, which were much more highly visible in the clear, thin air at 25,000 feet. We hit our Initial Point and from that time on the aircraft was under the control of the bombardier who followed the instructions of the radar operator. We began picking up some flak and some searchlights - all courtesy of our friends, the Soviets. At that time, the MiG-15s were flown almost exclusively by Soviet Air Force pilots. All the anti-aircraft guns and searchlights were manned by Soviets, too. Our national leaders were concerned that if we were allowed to bomb across the Yalu River in Manchuria, we would upset the Soviets and cause World War III. Back to the mission. We picked up some flak and some search lights were trying to pick us up as we approached the target but it was not heavy. Several flak bursts rocked the aircraft pretty good and we could hear the shrapnel rattling off the aluminum skin of our plane. Once our bombs were dropped, I had a great view of the explosions. We cleared the target area and the aircraft commander called for a crew check. This was done routinely every 30 minutes and always when clearing the target area on a combat mission. Upon his call the tail gunner always began the report and it moved forward thru the aircraft. I reached for my hand mike and tried to check in with a "tail gunner okay" message. I could tell by no sound in my headphones that I was not transmitting. I could hear the other crew members but they obviously could not hear me. Earlier the intercom in the tail position was working normally as were all the other crew positions. By now the aircraft commander had repeated his call for crew check and I could tell he was beginning to get agitated. After several more tries, he asked if anyone felt or heard a hit in or near the tail. No one had and he said "Well, maybe his oxygen has failed and he's passed out or even dead." Now that gave me an eerie feeling! I felt like I was dead and listening to the crew talk about me. Someone else chimed in with, "He's probably not dead, just asleep. You know how he likes to sleep!" That did not make me feel much better. The call box on a B-29 had a five-position switch. It also had a Call position which would override any of the other positions. I had tried every position, including Call, many times, all to no avail. The aircraft commander said, "Well I guess we'll have to depressurize and send somebody back to check on him." Finally Jim Eckols, the right gunner and my best friend on the crew, requested permission to go to the aft bulkhead door of the gunners compartment and look toward the tail to see if he could determine anything. This was granted and I realized this was my chance. I grabbed my GI flashlight, and got ready. Eckols checked in with the aircraft commander when he reached the aft bulkhead door. I held the flashlight down between my legs and hoped I was shining it thru the glass porthole of my pressure bulkhead door and that my friend could see it. Almost immediately Eckols reported, "I can see him flashing his flashlight so at least we know he's alive and he can hear us!" Then he hit on the idea of asking me to flash twice if I was okay which I immediately did. Then he asked me to flash three times if I needed for us to depressurize so they could get me out or flash once if I was willing to stay back there until we got to a lower altitude. I flashed once and then things began getting back to some semblance of normalcy. Today, over 50 years later, I get claustrophobic just thinking about that tiny, cramped tail gunner compartment and how long I sat there unable to stretch, stand up or really move anything more than my hands, feet and head. It's a good thing I did that when I was young, because I sure could not and would not do that today! Did it once and once was enough! The longest dam-busting mission.... Our longest combat mission was #14 on 12 September 52 . It was 12 hours and 40 minutes long and the target was the huge Suiho Hydroelectric Plant. The dam was across the Yalu River, the dividing line between North Korea and Manchuria. We were forbidden to violate Manchurian air space because the Soviets might take offense. As a result anytime we bombed such a target we had to fly a bomb run from west to east or vice versa. This meant a run along the length of the river rather than along the north-south length of the dam. Rather poor results usually occurred, but we didn't violate Manchurian air space. North Korea was completely blacked out. That night as we flew our bomb run from west to east I could see an airfield on the north bank of the Yalu in Manchuria . Runway lights were on and the ramps and surrounding buildings were well lighted. Many dozens of MiGs could be seen on the ground. They weren't worried about getting their airfield bombed. They knew we wouldn't violate their air space. Bold and daring, maximum effort daylight raid... Exactly one week later we flew the only daylight mission of our tour. It was a maximum effort by all three B-29 groups, the Far East Air Force's 19th, SAC'S 307th, also based at Kadena with us and another SAC group, the 98th flying out of Yakota AFB near Tokyo. The ground crews did a fine job and the three groups together put up over 90 B-29s in one formation. This was a remarkable feat for maintenance, considering the maximum number of B-29s allowed in the Far East at any one time was 99. Something about not offending the Soviets I guess.

It was a beautiful sight to see so many B-29s in one formation. Our aircraft was in the far left group of the formation, but as we formed up and later looking out the right blister I could see most of the planes. A three or four plane flight was about the biggest I / had ever been in prior to that daylight raid. We logged 10 hours and 40 minutes that day. The final mission jitters... The closer we came to the end our tour, the more apprehensive I became. The final combat mission of our tour was on Thanksgiving night, November 27, 1952 . The food in our 24-hour mess was usually pretty good but the noon meal that day was especially fine. We had turkey and dressing with all the trimmings, ham, lots of good bread, a good variety of vegetables and desserts, even salted nuts and other snacks. But we were apprehensive. We knew our mission that night was our last scheduled combat flight and the next day we would begin processing to clear the base and return to America. Naturally we thought about our first assigned B-29, Apache and what happened to her and her crew on their last scheduled mission before going home. Attempts at some gallows humor by some of our buddies who bellowed, "Eat, drink and be merry, gentlemen, for tomorrow you may die" did absolutely nothing to ease our concern. As usual, but in much larger numbers this time, there were men in groups at different spots along the taxiway, waving to us as we moved toward the runway and takeoff. The mission was easy. No flak, no searchlights, no fighters. The flight back from Korea to Kadena was a pleasant one. We brewed some hot instant coffee in our hot cups and ate sandwiches and desserts from the Thanksgiving dinner leftovers. Flying time for the mission was eight hours and 40 minutes. Taking the long way home, courtesy of the United States Navy... On December 3, 1952 , we took off from Kadena for the last time. We were flying a B-29 back to McClellan AFB in Sacramento, California . Before heading out over the ocean we gave the 28th Bomb Squadron Headquarters and Operations huts a buzz job to end all buzz jobs. Guys standing on the roofs of the quonset huts bailed off and hit the ground as we passed so low over them they thought we were going to hit them. Frankly, so did I. The crew consisted of our regular 11 flight personnel plus one passenger, Lt. Col. Raymond Buckwalter, the 28th BS commanding officer, who had completed his tour of duty at the same time as we did. The destination of the second leg of our flight was the tiny island of Kwajalein. About five hours away from touchdown our number two engine began running rough. Nothing seemed to help and we quickly shut it down and feathered the prop. The remaining hours passed uneventfully and our navigator, 1st Lt. George Collins performed his usual first class job and put us on the island perfectly. We landed late in the afternoon and after a really good meal in the Navy mess hall we spent the night in the transient barracks, wondering how long we would have to stay there. The next morning we discovered a crated B-29 engine back in one corner of a hanger. We found out it had been taken off a C-54 coming from the states and left at Kwajalein because of weight problems. Col. Buckwalter talked to a few people and using his rank to advantage got permission for us to put that engine on our Superfortress. At this point our real troubles began. The hangers on the airfield were not large enough to get the entire B-29 inside but the Navy said they would at least get the left wing under cover so they would have some shade while changing the engine. Navy personnel began moving equipment, maintenance stands, etc. preparatory to towing the aircraft under cover. One Navy man was moving a motorized crane used for hoisting engines and somehow the tall boom came in contact with some high power lines. The driver was electrocuted. None of our crew was there but we soon heard about it and went immediately to the hanger. Many Navy personnel were there and they blamed us for the man's death. Some were saying if we hadn't come in with a dead engine their friend would still be alive. No doubt true, but it wasn't as though it was our negligence killed him. We were deeply sorry but there was nothing we could do other than express our sorrow and condolences. We were told the next day that the Navy mechanics would be unable, after all. to change the engine. However, if we wanted to perform the engine swap we could do so. The big problem was that none of us were Aircraft & Engine mechanics. Our flight engineer had some hands-on experience but even that was somewhat limited and had occurred many years previously. However, our desire to be home for Christmas overpowered any reservations we had and after looking through the maintenance manual the flight engineer proclaimed, we can do it! Next problem! We had no tools and only after a high level conference between Col. Buckwalter and the top Navy commander did the Navy mechanics agree to loan us some of their tools. But only one at a time per man. When we finished with one tool it had to be returned before getting another. If a MATS plane needed mechanical attention, the Navy people gathered up all their tools and we had to wait until their return before we could resume our engine swap. We would gladly have worked on the engine change 24 hours a day, but the Navy limited us to 12 hours a day. Every man on our crew put in at least some time on the change, including our C.O. With our limited knowledge as well as limited time and tool use, it took us almost 12 days to complete the swap. The Navy gladly pushed the Superfortress out of the hanger and our entire crew was there for the moment of truth. Would the engine start? I'm not sure what went through the minds of the others but I really had no confidence that the big Wright-Cyclone radial would fire up and run. I do know that all of us were holding our breath and most were voicing a few prayers as the engineer and AC attempted to start our new number two engine. As usual the prop turned slowly and after a few revolutions the big radial belched some huge clouds of smoke, ran for a second or two, then stopped. Now all this was not unusual. In fact it was pretty much the norm for all those radial engines. The starter was energized again and this time when the engine began firing, it hiccupped a few times, blew back a lot of smoke and then settled down to a steady rumble. We all wore huge smiles. They ran the engine long enough to check all pressures, etc., then shut it down. We checked it thoroughly for oil and fuel leaks. Everything seemed to check out okay. so we made plans to finally depart Kwajalein the next day. Before we left the states heading for Okinawa on our trip out six months before, Capt. Locker asked if we had ever flown across the Atlantic or Pacific Oceans. Six or seven of us had not. He gave us this friendly warning; You're going to see nothing but miles and miles of nothing but miles and miles. And he was sure right. The boredom was worse going back. At least coming over we could lie down in the stretchers on the C-54 ambulance aircraft and sleep a lot. Coming back most of us had to stay awake most of the time. However, we did swap off some so everyone got some sleep in flight. The boring routine was again broken a few hours out of Hickam AFB, Honolulu , when number three engine began leaking oil. We were not leaking oil fast enough to shut down the engine, but enough to be concerned. After landing, mechanics checked it out and said it could be repaired but it might take them 24 to 30 hours. We didn't mind spending the extra time in Honolulu, especially since we wouldn't have to do the work. Two days later we left Hickam on our final leg. Next stop, the U.S.A. Not long after the point of no return, the weather took a turn for the worse. Conditions over the McClellan AFB area were predicted to be totally socked in within the next three to four hours. There was no way we could get to McClellan before that so we were diverted to March AFB, Riverside, CA . We landed there shortly after dark and sat around the transient lounge for about 12 hours. Capt. Locker kept checking the weather and shortly after daylight they said the fog at McClellan might lift briefly in about three hours. The Superfort had been refueled as soon as we landed, so we took off as soon as we could and headed north to McClellan.

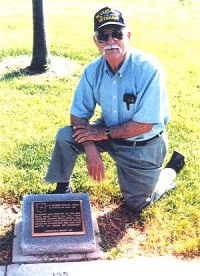

We flew above McClellan for almost four hours waiting and hoping the fog would clear. It stayed below Ground Controlled Approach minimums. We did let down into it one time but it was like flying into a huge bowl of pea soup. There were several other aircraft flying in the clear blue sky above the soup and occasionally one would let down into the stuff. It was as though the aircraft was flying down into a white ocean. A few minutes later we could see the plane climbing back out of the fog bank. McClellan air control finally told us the field at Travis AFB was reporting GCA minimums and if we hurried we may be able to get in there. We did manage to get on the ground there, the last aircraft to land before they shut the field down again. We were on the ground but not at McClellan where we had to deliver the Superfort. We stayed at Travis almost two full days but no aircraft were allowed to take off or land. By now it was December 21st and the five remaining members of our crew had just about given up hope of getting home for Christmas. Shortly after landing two days before at Travis, Capt. Locker had released six crewmembers to depart for home. Col. Buckwalter had also left. Still there at Travis were Locker, Lt. Jim King, pilot, MSgt. Charles Ragsdale, flight engineer, Sgt. Jim Eckols, right gunner and me, Sgt. Clyde Durham, left gunner. These were the positions required for a B-29 flight of short duration. Late in the day on December 21st, Locker called us all together and gave us the good news. He had found a B-29 crew stationed at Travis that was not going anywhere for Christmas and they had agreed to fly our plane to McClellan as soon as weather permitted. I never met any of those men, but I shall be eternally grateful. The civilian airlines were very helpful and managed to get all of us on flights home early the next day. I could get no closer than Dallas, but I was grateful for that. Once in Dallas, I got a bus to Shreveport , LA. My family drove the hundred miles to there from Alexandria and met me at the bus station. I was finally home on the 22nd of December, after leaving Okinawa on the 3rd of the month. It was about the best Christmas I ever had. There was a girl named Barbara Simmons with my family to meet me in Shreveport and on January 4, 1953 we were married. We had gone together since our high school days and we're still together today -- three daughters and seven grandchildren later. The thrill of a lifetime... My tour of duty in the 28th Bomb Squadron only lasted a little over six months but as long as I live the 28th and its personnel will hold a very special place in my heart. I have had the privilege of meeting a number of current 28th BS people and visiting squadron headquarters. Today, the 28th flies the magnificent B-1B supersonic, multi-role bomber. I even got a chance to "fly the Bone" in a simulator myself during a recent visit to the unit training HQ at Dyess AFB in Abilene, Texas. It was a thrill of a lifetime and an experience I will always cherish. The 28th Bomb Squadron today...

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

At 1000

hours Sunday, 25 June 1950 Far East Air Force Headquarters received word of the North Korean attack on South Korea

. About six hours earlier the North Koreans had slashed across the 38th parallel and the South Koreans were being

totally routed. That afternoon, the United States Air Force was at war again. President Truman ordered Gen.

Douglas MacArthur to send the Air Force and the Navy to battle.

At 1000

hours Sunday, 25 June 1950 Far East Air Force Headquarters received word of the North Korean attack on South Korea

. About six hours earlier the North Koreans had slashed across the 38th parallel and the South Koreans were being

totally routed. That afternoon, the United States Air Force was at war again. President Truman ordered Gen.

Douglas MacArthur to send the Air Force and the Navy to battle.

As was the custom, crew members on

their first combat mission were flown as extras or replacements on a veteran crew. Not until the second or third

mission did a new crew fly as a unit together. With us it was our second mission that we flew as a crew with only

an experienced pilot as observer. It was on a B-29 named Island Queen.

As was the custom, crew members on

their first combat mission were flown as extras or replacements on a veteran crew. Not until the second or third

mission did a new crew fly as a unit together. With us it was our second mission that we flew as a crew with only

an experienced pilot as observer. It was on a B-29 named Island Queen.

The aircraft first assigned to us was one named Apache. She was the B-29 with the sexiest

nose art in the unit that featured a scantily clad and gorgeous Native American woman perched on a tom-tom. She

was a veteran warrior, We got word of our assignment shortly before lunch one day. After chow we went to the

squadron area and found Apache. Her regular crew was flying a mission that night and the hot guns position showed

the gunners had already completed their preflight and left the hardstand.

The aircraft first assigned to us was one named Apache. She was the B-29 with the sexiest

nose art in the unit that featured a scantily clad and gorgeous Native American woman perched on a tom-tom. She

was a veteran warrior, We got word of our assignment shortly before lunch one day. After chow we went to the

squadron area and found Apache. Her regular crew was flying a mission that night and the hot guns position showed

the gunners had already completed their preflight and left the hardstand.

A total of 45, B-29s made up

the main bomber force. Three B-29s attacked before the main force hit, dropping airburst bombs in a

flak-suppression role. After that attack, they orbited the area above the main force using electronic

countermeasures (ECM) against the radar-controlled guns and lights. In addition, seven B-26s flew low-level

searchlight suppression attacks prior to the main force attack.

A total of 45, B-29s made up

the main bomber force. Three B-29s attacked before the main force hit, dropping airburst bombs in a

flak-suppression role. After that attack, they orbited the area above the main force using electronic

countermeasures (ECM) against the radar-controlled guns and lights. In addition, seven B-26s flew low-level

searchlight suppression attacks prior to the main force attack.

B-26s went in low on flak suppression

attacks and we had a high cover of F-86 Sabre Jets for protection against the MiGs. The target was a troop,

material and rail marshalling yard center and went off pretty well as planned. We got some light to moderate flak

but were never hit by the MiGs. Some MiG-15s tangled with the Sabres, but we never heard the results.

B-26s went in low on flak suppression

attacks and we had a high cover of F-86 Sabre Jets for protection against the MiGs. The target was a troop,

material and rail marshalling yard center and went off pretty well as planned. We got some light to moderate flak

but were never hit by the MiGs. Some MiG-15s tangled with the Sabres, but we never heard the results.

By Mad Max Merlin, Combat Flight Simulation Editor

By Mad Max Merlin, Combat Flight Simulation Editor